(03:14:08 UTC on 19 January 2038)

01111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

(20:45:52 UTC 13 December 1901)

10000000 00000000 00000000 00000000

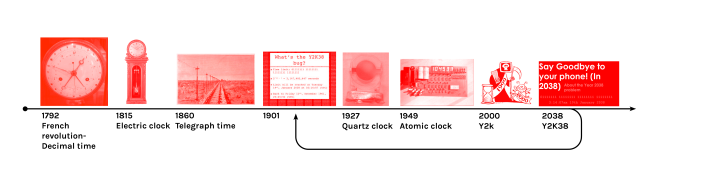

In Walter Benjamin’s Thesis on the Philosophy of History, he testifies that “on the first evening… of the July revolution”, the clock towers in Paris “were being fired on simultaneously and independently from several places.” The French conceived of Revolution as being against the material regimes which signified time itself; on the 5th of October 1792, the National Convention officially introduced decimal time, each day split into 10 hours and each hour into 100 minutes.

The introduction of decimal clock was overrun by the vast expansion of Greenwich Mean Time. Through the extension of the railway networks, the necessity of keeping a standard time not based on sunrise and sunset spread through Europe. Through these networks, the telegraph expanded through the United Kingdom, enabling a signal for standard time to be sent nationwide from Greenwich.

In more recent times, the materiality of time has confronted us in the realm of digital timekeeping. The widespread anxiety about the Y2K bug in 1999 triggered bank runs, worries about medical equipment, and the publication of “The Y2K Personal Survival Guide”.

The next disruption of time’s materiality will occur in 2038. The ‘2038 problem’, as it has been named, will affect every system with embedded on UNIX 32-bit dates, including many file systems, monitoring subsystems, Android phones, assorted medical- and military systems, and transportation systems including electronic stability control, four-wheel drive, and GPS receivers. The problem is based on the 32-bit code that signifies dates: on the 19th of January 2038, the code will ‘run out’ of bites and reset from to signify the 13th of December 1901.

According to Eric Alliez, “the time of presentation is put outside itself in the representation of time”. Because technologies are quick to become obsolescent, the standardisation of time has consistently failed to envision the near future. Material timekeeping regimes undermine time’s representation in itself.

not bibbed

LikeLike

edited

LikeLike